Sudden, accidental, unexplained or suspicious deaths – The Coroner and their records – Part One

- 5th April 2025

Since 1194 Coroners have existed to investigate unnatural, sudden or suspicious deaths, and of deaths in prisons. The function of Coroners, their status and relationship to the state has changed over time and this has affected the type and survivability of records which exist today. For instance, you are more likely to find a newspaper report than a Coroners’ record during the hundred years before the Second World War. In this first blog, we outline the role and duties of the coroner in the past and within contemporary society and their role in inquests.

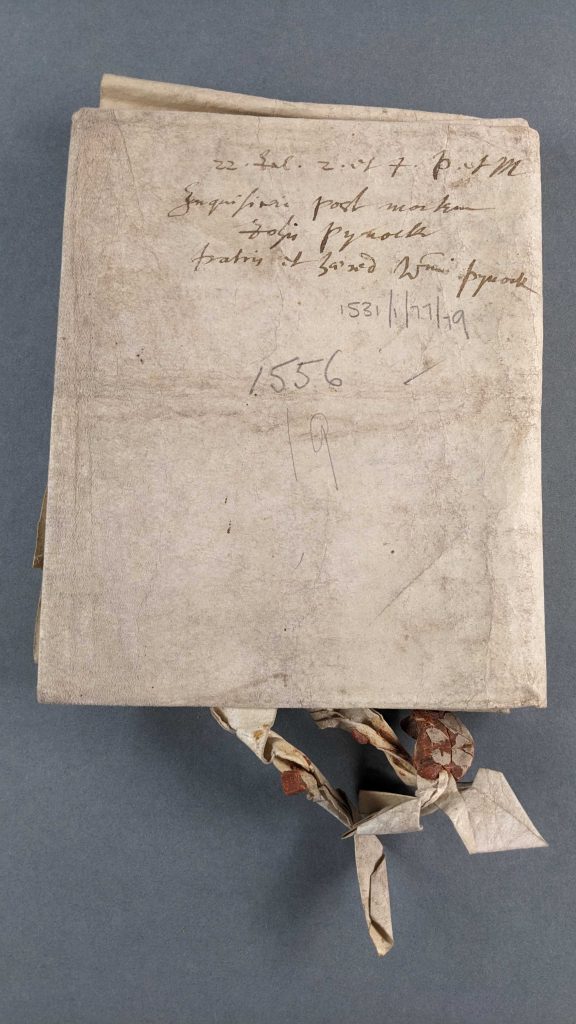

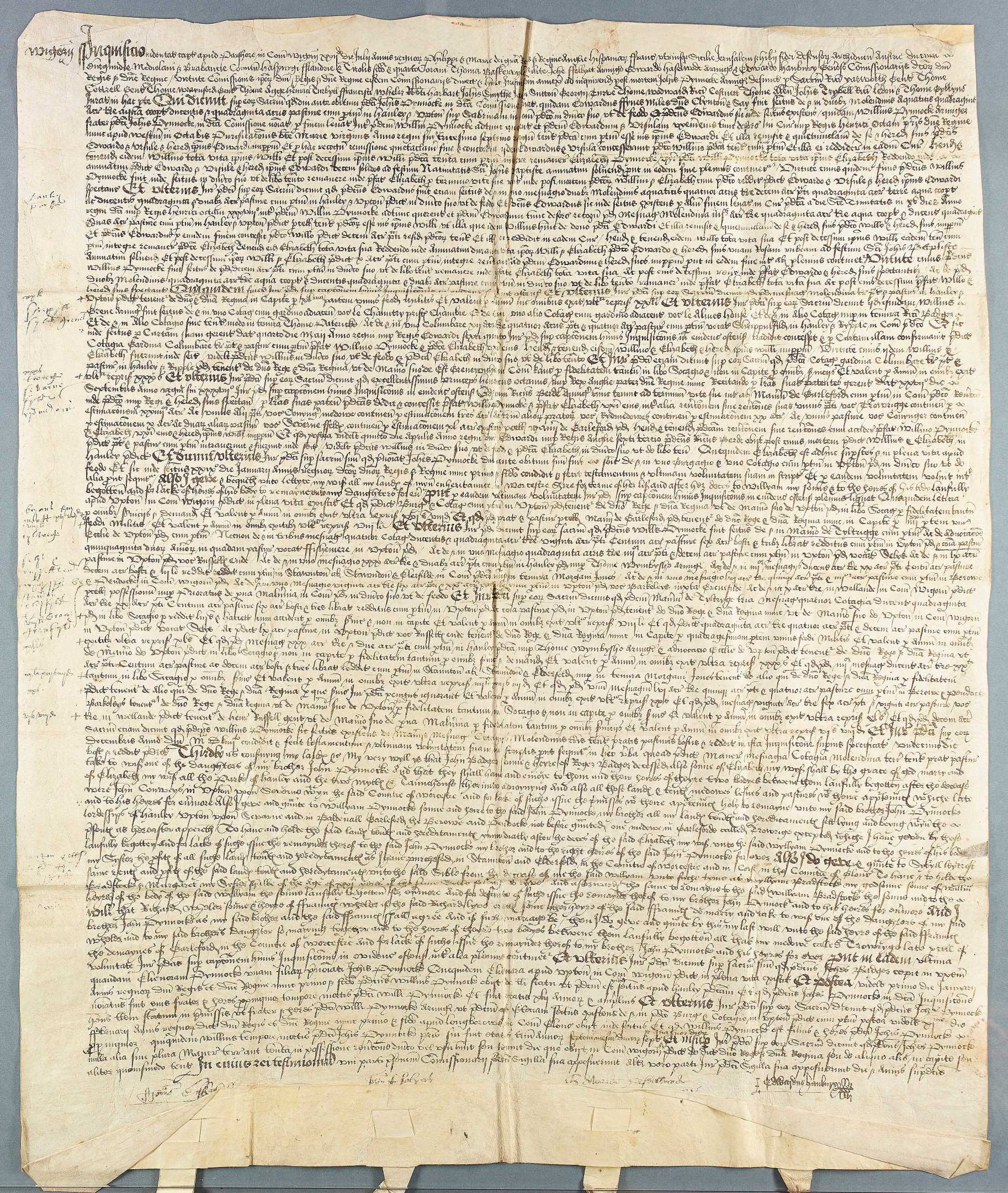

Medieval coroners held a relatively high social status and in the earliest days were expected to have been knights. An Inquisition post mortem held in our archive at Finding No: 705:134 whilst not directly referring to coroner’s inquests or examinations is an inquiry into lands owned on behalf of the crown, following the death of a tenant in chief. In this case, John Pynock for crown lands in Hanley and Upton upon Severn. When the chancery heard of the death of a tenant in chief, a writ of diem clausit extremum (‘he closed his last day’) was drawn up, ordering the escheator (the royal official who held the inquest locally) to hold an inquisition in his county.

Inquisition post mortem [shown folded] of John Pynock, Knight, 22nd July 1556 Finding No: 705:134 BA1531/77/79

Depending on the holdings of the deceased, writs could have been issued to the escheators of multiple counties. Each writ gives the name of the deceased and instructs the escheator to take the lands into the king’s hand, to summon a jury of local men to answer a series of questions relating to the extent, tenure and value of the lands, properties and rights of the deceased, and to identify the nearest heir. The inquisition also contains detail concerning the deceased family members, so these Manorial documents can be useful for family history researchers.

Whilst Coroners held inquests on dead bodies they also dealt with felons’ abjurations of the realm and appeals and declared lawlessness in the county court, though did not normally deal with so-called treasure trove (or wreck of the sea and royal fish) until after the Civil War. From the 14th century, their status declined, so that from Tudor times, almost their only function was holding inquests on dead bodies and their only qualification for six hundred years (1340-1926) was to be a landholder. Until 1926, no coroner was required to have medical or legal qualifications, and all inquests were held with a jury more akin to the grand jury rather than to that of a petty (trial) jury and could vary in number from 12-24, with numbers reduced to between 7-11 with no more than two dissenting.

A useful guide to Coroner’s Records in England and Wales is held in our Reference Collection at L347.016 by Jeremy Gibson and Colin Rogers.

It was common practice from 1487 to 1752 for coroners to hand over records of all inquests to assize judges. Those which resulted in verdicts of murder or manslaughter (including many that would now be regarded as misadventure) are normally found in the indictments or depositions files of the relevant assizes circuit. You can learn more about the assizes courts here. From 1752 to 1860, coroners were required to file inquests at the Quarter Sessions, and so they may be preserved among the records of Quarter Sessions, at local or county record offices. You can learn more about Quarter Sessions records here. From June 1752, coroners were offered one pound for every inquest held outside gaols and ninepence a mile for their journey from their home to the body. As we shall see later, in the 19th century, it wasn’t uncommon for coroners’ inquests to be heard in public houses, alongside the houses of the deceased families.

What is the Coroners role today?

As defined by the Ministry of Justice in their Guide to a Coroner Services for Bereaved People, ‘a coroner is a special type of judge appointed by a local authority to investigate certain deaths. Coroners are usually lawyers, but sometimes they can be doctors. Coroners work within a framework of law passed by Parliament. They are appointed by a local authority but remain independent judicial office holders.’

As stated on the WCC Coroners’ service homepage, the role of the Coroner is:

‘to investigate and record the causes and circumstances of all sudden deaths where the cause is not known, violent or unnatural deaths and any death which occurred whilst the deceased was in lawful custody’.

The coroner service is headed by the Chief or Senior Coroner and includes several Assistant Coroners or Coroners Officers. Often, these people will be referred to as ‘the coroner’s office.’ In the event of a sudden death, the Coroner will be informed either by the Police, the ambulance service or the GP, with initial enquiries undertaken by one of the Coroners officers. Coroner’s officers are members of staff who work for coroners and provide a link between the coroner and the bereaved person (or witness).

Worcestershire Conquest Hoard recently displayed at Worcester Museum and Art Gallery © Anthony Roach

Treasure Trove

Apart from their role in investigate certain deaths including inquests, you may not be aware, but coroners are also the named Officer to be contacted, if treasure is found, such as those discovered by the public such as metal detectorists, where they have been given permission to detect on land by a landowner. Treasure trove records of the Coroner concern those which report an investigation into whether gold or silver objects have been hidden when their true owner was unknown and include statements of witnesses and the outcome of the cases are given.

A recent example of treasure found in Worcestershire is that of the Worcestershire Conquest Hoard that was recently displayed at Worcester Museum. You must report items officially defined as treasure, either with 14 days of first finding it or within 14 days of realising an item might be treasure. Failure to report a find of treasure could lead to an unlimited fine or up to 3 months in prison. You can learn more at Report Treasure.

What is an inquest?

An inquest is a public court hearing held by the coroner to decide who died and how, when and where the death happened. Historically, these were known as an Inquisition and might be the only record of an inquest. From 1487 many were forwarded via the assize justices, to the King’s Bench, which are available at The National Archives. It may be held with or without a jury, depending on the circumstances. At the inquest the Coroner will hear from witnesses and consider other evidence such as post-mortem or expert reports. Not all deaths which are investigated by a Coroner need to have an inquest. You will be told when an inquest is required.

An inquest is different from other types of court hearing because there is no prosecution or defence and only the coroner can decide what evidence to hear. As the purpose of the inquest is only to discover the facts of the death the Coroner (or jury) cannot find anyone criminally responsible for the death. However, if evidence is found that suggests someone may be criminally responsible for the death, the coroner can pass the evidence to the police or the Crown Prosecution Service. Similarly, the coroner (or jury) cannot find someone liable under civil law. These are matters for other courts.

The Coroner under Regulation 27 of The Coroners (investigations) Regulations 2013 must keep records in relation to postmortem and Investigation’s for a minimum of 15 years. Should an inquest be required a paper file will be produced, and the inquest file may be retained indefinitely within the county archives. The conclusion of an inquest is a matter of public record, and any person can request a copy of a death certificate from the Registrar’s Office. A summary of inquests which have taken place, including verdicts, can be viewed on the Coroners website.

Interesting examples, thanks!