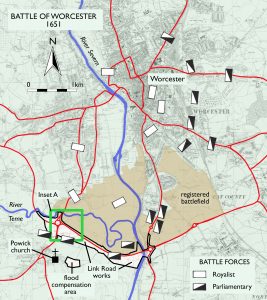

On September 3 1651 Charles Stuart (later to become King Charles II) was defeated by Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentary forces at Worcester, ending his campaign on that occasion to gain the crown. A famous victory for Cromwell, the battle had begun on a floodplain south of the city, focusing on Powick Bridge over the River Teme, which otherwise barred his route to Worcester west of the River Severn. A unique opportunity to examine this part of the battlefield arose in 2017–22, when 1.9km of the A4440 Worcester Southern Link Road was dualled. The original road had been built in 1985 without archaeological investigation, and, curiously, it had later become the southern border of the Historic England-registered battlefield, even though the arena was known to extend across fields further south.

Map highlighting where fieldwork took place

Previously, only very occasional stray finds had been reported around Worcester which might have related to the Civil War. Back in 2017, therefore, there was one question at Worcestershire Archaeology: how should we set about looking for anything surviving from this battle – especially as it had ranged across such a large area and in a landscape known to be covered with a great depth of alluvium? Were the remains (if indeed any had survived) just present in the topsoil, as with the majority of battlefield sites? Or were they deeply buried, and so out of reach of the new construction works? A significant area of the battlefield was due to disappear under roadworks, so we took an unconventional and experimental approach. It succeeded: we found the battle.

Archaeological investigations in progress for Worcester’s Southern Link Road scheme.

Locating the field

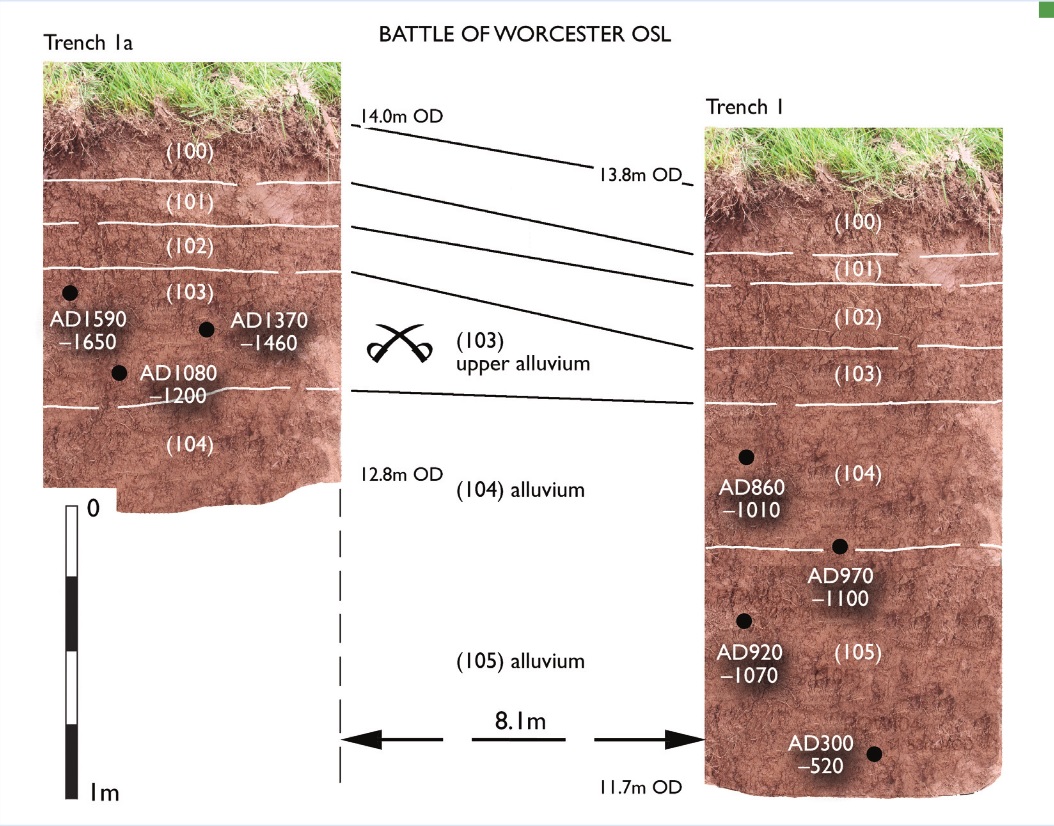

Having expected no large defensive structures, we had discounted geophysics and, at first, the usual evaluation trenching was undertaken. This was mainly to test for the presence and depth of mapped historic boundaries; any battlefield remains would be a bit of a hit-and-miss target as the actual ground on which the armies had fought is no longer the surface today, but lies beneath more recent river alluvium. The breakthrough came when we considered optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating, which makes it possible to calculate when tiny quartz grains within the alluvium were last exposed to sunlight before being buried (the longer away from light, the more electrons become trapped in the mineral’s structure). If we integrated OSL sampling within the trial trenching, could it define a buried 17th century horizon? Information of this type existed for deeper alluvium elsewhere within the Severn valley, but the technique had been little used for such recent periods. It would be a novel approach to seeking a historic battlefield.

Sample being taken for optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating by the University of Gloucestershire

The first OSL results (Trench 1) were distinctly encouraging, so Phillip Toms, professor in physical geography at the University of Gloucestershire, collected a second batch of samples that extended into the very uppermost part of the alluvium (Trench 1a). The highest sample returned a date of AD 1590–1650, suggesting that the upper few centimetres of the upper alluvium had potentially formed during the mid-17th century. We could now set a site strategy, targeting this location for artefact recovery. However, we needed to be cautious about applying this information too broadly. This became clear as the site work progressed, and better preservation was identified where more traditional water meadows had continued beyond the 17th century. Fortunately, this better preservation applied to much of the land closest to the route of the road widening.

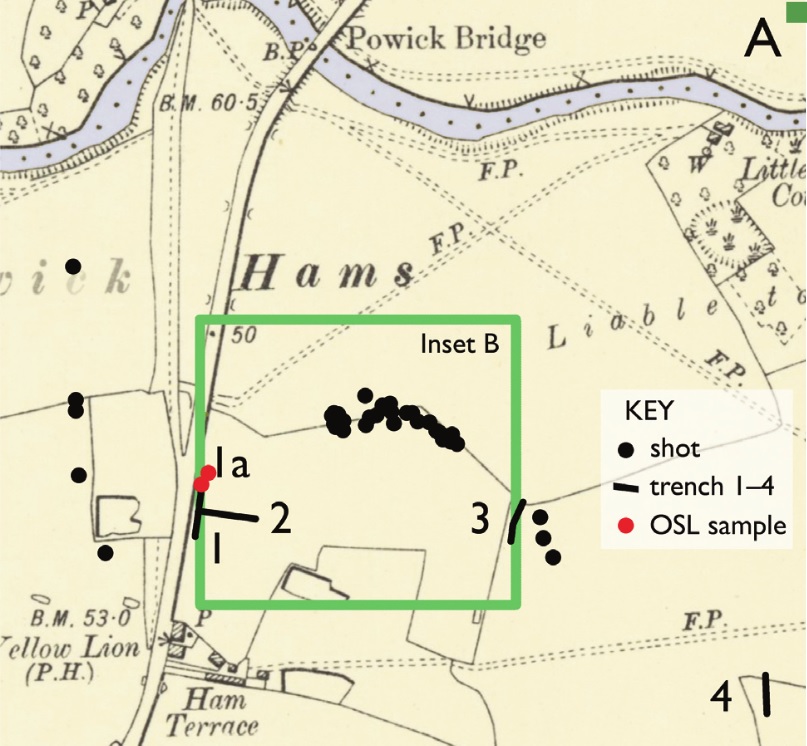

Now we knew where to look, investigations concentrated on metal detecting the pinpointed level as it became exposed during construction work. Previous items from the battlefield haven’t been securely located, so this was a rare and valuable opportunity to carefully map and record the physical evidence of such a significant event. In the hands of Dean Crawford, a very experienced detectorist, finds rapidly emerged from this horizon compatible with battlefield action. A high proportion of these were lead shot, most commonly musket balls. Eventually, it also even became clear that their spatial distribution corresponded with landscape features as observed on the earliest available historic mapping, particularly coinciding with field boundaries.

Alluvial layers marked with OSL sample dates, showing how the battlefield level was identified (created by British Archaeology magazine with information from Worcestershire Archaeology)

Searching for artefacts

We examined two main areas: the footprint of the new dual carriageway, which, being on a high embankment, was much larger than just the road itself, and a large lagoon established to its south as a flood compensation area (FCA). The latter turned out to be heavily disturbed due to potato growing, an intensive form of agriculture; this had clearly reworked the upper alluvial horizon. As a result, artefacts found here were abundant within the topsoil and less well preserved. The area along the line of the new road, however, turned out to be productive in quality data, where finds were in a sealed context and still largely in situ from September 1651.

Overall, we recovered a total of 50 lead shot, all compatible with Civil War period weaponry: including 30 musket balls (infantry weapon), all of slightly varying size; ten pistol shots and five carbine shots (both representing cavalry weapons); and two buck shots (used in multi-ball loads). Due to the lack of standardisation for firearms during the civil wars and a resultant overlap in shot size, identification of the weapon can sometimes be ambiguous. However, most of the musket shot appears to have been for use with “bastard” muskets (considered to be a smaller, lighter, more compact version that could be used without a rest), rather than a medium or full bore, though all sizes were present.

Clockwise from top left: Lead shot from a carbine (left) and musket (right), powder charge caps, strap ornaments and a buckle

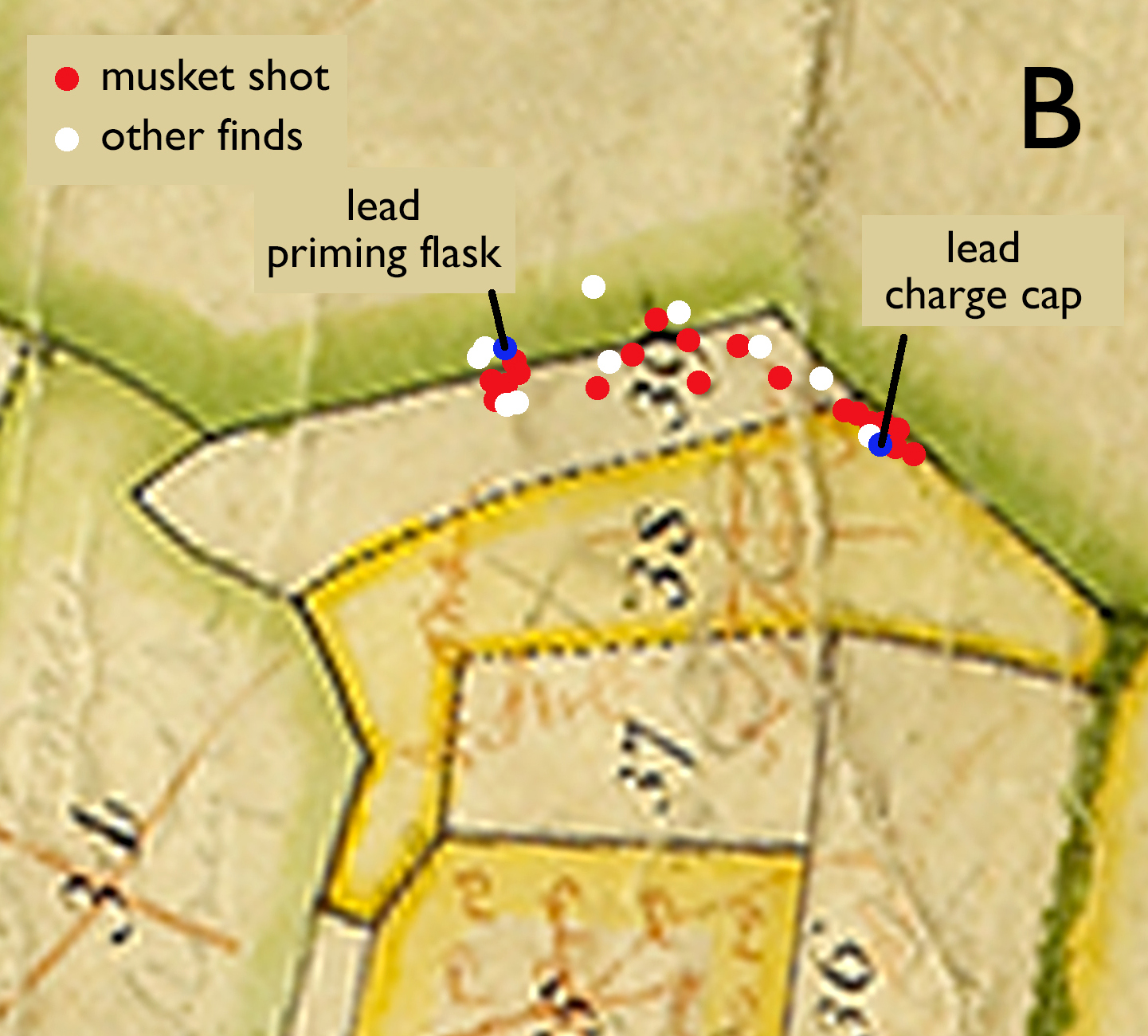

The largest spread of musket shot was found within the upper alluvium grouped together (along with other items) in the vicinity of a former boundary ditch some 140m east of the old route to Powick Bridge. Many exhibited evidence of their manufacture, but only some had indications of being fired; it is possible they had been dropped while this boundary was being used as a defensive position. The fumbling of fingers in the effort of reload as the enemy advanced can well be imagined, and so this cluster may be a vivid memento of the battle in this area at its height.

We also found powder charge caps, characteristic of late 16th to earlier 18th century battlefields. These were used to cover the top of a wooden cylinder containing a single charge of gunpowder, 12 being kept on a bandolier carried by a musketeer. One cap was found stratified in the upper alluvium among the cluster of musket shot by the field boundary mentioned above, where a lead priming flask nozzle was also found. Apart from miscellaneous lead pieces possibly carried by troops for melting down and recasting, there were several horseshoes, coins and at least one spur that could also be Civil War period losses.

Click on the side arrows to move left or right through the images. Hover over or tap on an image to pause.

Hedge to hedge

While the Worcester finds are comparable to those from many other Civil War battlefields such as Edgehill (1642), they are notable for being the first to be systematically recorded as (largely) in situ from a sealed horizon – in this case within an alluvial layer – and, therefore, retrieved directly from an intact 17th century landscape. The two main areas of investigation revealed particular information about the course of the battle. According to documentary sources, the approach route between Powick village and the bridge over the River Teme was heavily contested, becoming a major frustration for the Parliamentary advance. Here the hedged lanes, ditches and small strip fields are thought to have slowed the movement of troops, particularly cavalry. Finds from the western side of the old lane leading to Powick Bridge included a low-density grouping of pistol and buck shot, as well as a lead token, a horseshoe and clay pipes, perhaps suggesting that cavalry had tried to stay off the roadway (it was too narrow anyway to be a useful means of advance).

Map showing shot and other battlefield finds south of the River Teme, near the lane to Powick Bridge (created by British Archaeology magazine)

To the east of the road, a high-density concentration of artefacts was directly associated with a former field boundary. Here, the numerous lead shot was all from muskets (appearing mostly to have been used with “bastard” muskets), demonstrating an infantry confrontation. Other finds from this area included a powder charge cap, a priming flask nozzle, rolled lead, worn (illegible) copper-alloy coins, pewter plate, a horseshoe and fragments of iron, which, in combination with the musket shot, probably indicate that this was part of a defensive position. The occupation here of a boundary, likely comprising a ditch and a hedgerow, (a slight ditch may have been a later replacement boundary),correlates well with primary descriptions referencing “hedge to hedge” fighting that required close engagement: a Parliamentary Pamphlet of 1651 recorded that “all… advanced towards the Enemy, who had lined their hedges thick with men”; while a contemporary letter says that “the dispute was from hedge to hedge, and very hot; sometimes more with foot than with horse and foot”.

Map inset B, showing how battlefield finds seem to respect a field boundary on an 18th century estate map

Church tower

Further south, on the land used for the lagoon in the vicinity of Powick church (the FCA field), a mixed assemblage of lead musket, carbine and pistol shot, alongside numerous other associated finds – such as 16th and 17th century silver coins, a buckle, harness mounts, horseshoes, a spur, clay pipe and a powder charge cap – suggests that multiple troop types were active here. Proportionally pistol and carbine shot dominated this cluster, indicating cavalry. A significant number of the pistol shot had been fired and hit hard surfaces, and another shot that was probably a musket ball was heavily impacted and distorted: these were all near a historic field boundary close to a small track heading around the south and east sides of the higher ground occupied by the church. From its tower, which itself has scars from musket shot, and which some sources suggest was used as an observation post, Royalist troops had vainly tried to hold back the Parliamentary army.

Royalist musketeer from a Scottish regiment (above)

Parliamentarian cavalry soldier (below left) and pikeman (below right)

Click on the + buttons to read the labels.

Major benefit

On most battlefields, the material residue of conflict is to be found in the ploughsoil, and, as a consequence, is readily accessible for general metal detecting, and has been disturbed through agricultural and other activities. By contrast, the evidence for the Battle of Worcester has turned out to be surprisingly intact, much of it even where it fell to the ground, in the heat of battle. The location of this part of the battle within the alluvial landscape of the River Severn and River Teme floodplain has, therefore, turned out to be critical for protecting archaeological evidence of that fateful day. Significantly for the survival of this material, this productive level is today beyond the reach of metal detectors used at the surface, thereby preserving it for future detailed archaeological recording.

Musket ball as excavated showing its burial in the upper flood silts

Strictly speaking, the numbers of finds may not seem that great for such an engagement, but interventions by the development were relatively limited, given the great size of the battlefield. When quantities are extrapolated across its full extent, they can be seen as potentially considerable. More information lies waiting below our feet, and we now know how to find it.

This piece is based on an article by Derek Hurst and Richard Bradley, first published in the January/ February 2023 issue of British Archaeology magazine. Historical battle commentary mainly follows Malcolm Atkin’s The Civil War in Worcestershire (1995). The project was undertaken by Worcestershire Archaeology for TACP (UK) Ltd, working on behalf of Alun Griffiths and Worcestershire County Council. The University of Gloucestershire carried out the OSL dating and Abbie Horton (Worcestershire Archaeology) created the reconstruction solider drawings. Photos and figures are copyright of Worcestershire Archaeology, unless otherwise stated.